Is this the story of a name, or a person? I’ll let you decide…

The year was 1942 and the cobblestoned streets of Agii Deka were hard beneath the boy’s barefeet. The fig trees had been picked clean, the last plums were used for jam, and the blackberries had all dried out. Food was nowhere to be found.

At the edge of the village, the boy stopped to take in the view. Agii Deka sat at the top of a small mountain overlooking the whole north-eastern coast of Corfu, so it was a view the boy often returned to. Cypress trees lined the hills, erupting from the lush forest that rolled down to the coast. The glittering blue sea met the island with a soft caress, rippling with pleasure and swaying back and forth in the sunlight.

Corfu Town – the big city, with all its church spires and towers – was down there too. It was a strange place. The boy and his mother would go there often to sell vegetables from the garden. They’d both walk the 12km down the mountain without any shoes, then at the end of a long day’s selling, they’d trudge back up with their leftover veggies.

The boy might have been young, but even he noticed that in Corfu Town, everyone wore shoes.

The money made from selling vegetables wasn’t for shoes, though. It was for surviving. The boy was not the only child in the family. He had three siblings: two sisters and one brother. And both of those girls needed a dowry in order to get a decent husband. Not to mention, one of them was sick and barren. For her to be married, they’d need an even bigger dowry.

So no. No shoes for the boy. He was the eldest anyway. He was big enough and tough enough to not need shoes. He had to support the family, look after his siblings, watch over his mother while his father was away.

Talking of which, his father was the talk of the village. He was a baker, and his moustokouloura (a local type of biscuit) was the tastiest in Agii Deka. He would sell them during the daytime, and travel to local villages at times of festivals to increase his sales. But even if they were the best moustokouloura in all of Corfu, there’s only so many biscuits one man can make and sell in a day. And there’s only so much money a peasant is willing to part with for a biscuit. And that was before the war.

But back to the boy – or the Golden Boy, you might call him. His stomach empty, his feet calloused, and his country teetering on the brink of war, his mind was elsewhere. On girls, of course. You see, he wasn’t just a Golden Boy for the family. He was popular among children his own age too. They looked up to him. He was a natural leader, full of creative ideas, wit, and a seemingly inexhaustible tank of energy.

And when the Italians marched on Greece and war was declared, he put that excess energy to good use.

You see, the Italians came to Corfu in ships. The boy was too young to properly understand who they were, or why they had come, but he wasn’t stupid. The Italians brought horses, the horses had grain, and their grain was the same damn grain that his mother used to bake bread – that warm fresh bread that smells almost as good as it tastes.

So when the boy, from his regular vantage point, spotted the ships on the coast, he concocted a plan. He obviously had to be careful. These were armed soldiers and they had all sorts of weird machinery too. Would they kill him if they saw him? Would they torture him or enslave him? He couldn’t say.

“Don’t get going near the soldiers,” his mother had told him. “The further you are from them, the better.”

She wasn’t the only one to warn him. Seemingly half the village had said it at one point or another. By the end of his daily lectures, the point was abundantly clear: soldiers = bad.

But he was oh so curious. He could almost smell the freshly baked bread and the heavenly aroma wafting around the house. He could feel the pleasure of tearing a chunk off and seeing the soft and fluffy insides steaming. The whole family would be happy and full.

Plus, he wanted to see these soldiers a little closer. They were new and exciting. They had guns. He was quick enough and clever enough to not be seen. Right? He wasn’t the all-time dare devil of Agii Deka for nothing! The kids looked up to him – he couldn’t let them down now. There would be enough grain for everyone!

And so the dice was cast: alea iacta est.

In the dead of night, a terrified whinny tore the Italian soldiers from their makeshift beds. A shadow scurried through the forest, lugging something in its hands.

Was it an ambush?

One soldier went to follow, but halted. The forest was dark – and the invaders were in unfamiliar territory. If the locals lured them into the hills at night, they could be picked off one by one.

The horse whinnied again, nudging the place where its feeder had been. Realising the grain had gone, the soldiers relaxed somewhat and returned to a twitchy sleep.

Back in Agii Deka, there was bread for everyone. Even though the boy’s mother had warned him not to play near the soldiers, she couldn’t help but be proud. The whole family went to bed with a full stomach, and the boy’s imagination drifted to future adventures.

Hopefully the soldiers would stay longer and they’d replenish the grain, and the boy could go down and steal it again. Things were starting to look up.

That’s when the soldiers appeared in the village. The following morning, they rolled in with their guns. Were they looking for someone? How did they know the culprit was from Agii Deka? Could they recognise the bread?

Suddenly, the whole thing felt like a bad idea. They intimidated the locals. Even the biggest men in the village cowered before them. They looked kind of like Greeks – maybe from a different village. And they all had shoes. They were fascinating and terrifying all at once.

But the soldiers didn’t ask questions about grain. Or if they did, nobody could understand them. They spoke in a sing-song kind of language that nobody could comprehend. But as the soldiers looked down from the same viewpoint as the boy had, watching the forest slope into the shimmering sea, one Italian phrase stuck in his mind like a thorn: “Che bella vista!”

Over the next few months, soldiers visited Agii Deka regularly. Were they looking for human interaction during the atrocities of war? They must have noticed that the Corfiots could easily have been Italians – maybe they were reminded of little villages in their own country.

During this time, the Golden Boy quickly picked up the sing-song language. In fact, he became a translator for the Italian soldiers. He jumped at the opportunity to trade his garden vegetables for grain. He didn’t just trade for himself either. He traded on behalf of the entire village.

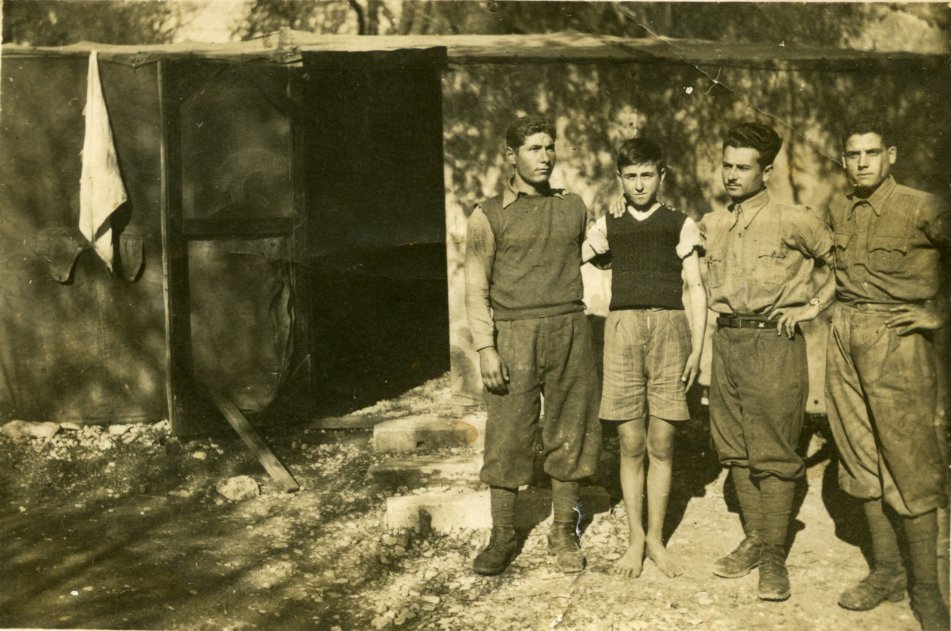

The Italians had something else, too. Something the boy had never seen before: a camera. One day, somewhere in Agii Deka, one of the soldiers asked the boy to stand still. The boy didn’t understand what they were doing, but he obeyed. After a loud click and a jarring noise, the soldier with the camera handed the boy a photograph.

“Memory,” he said.

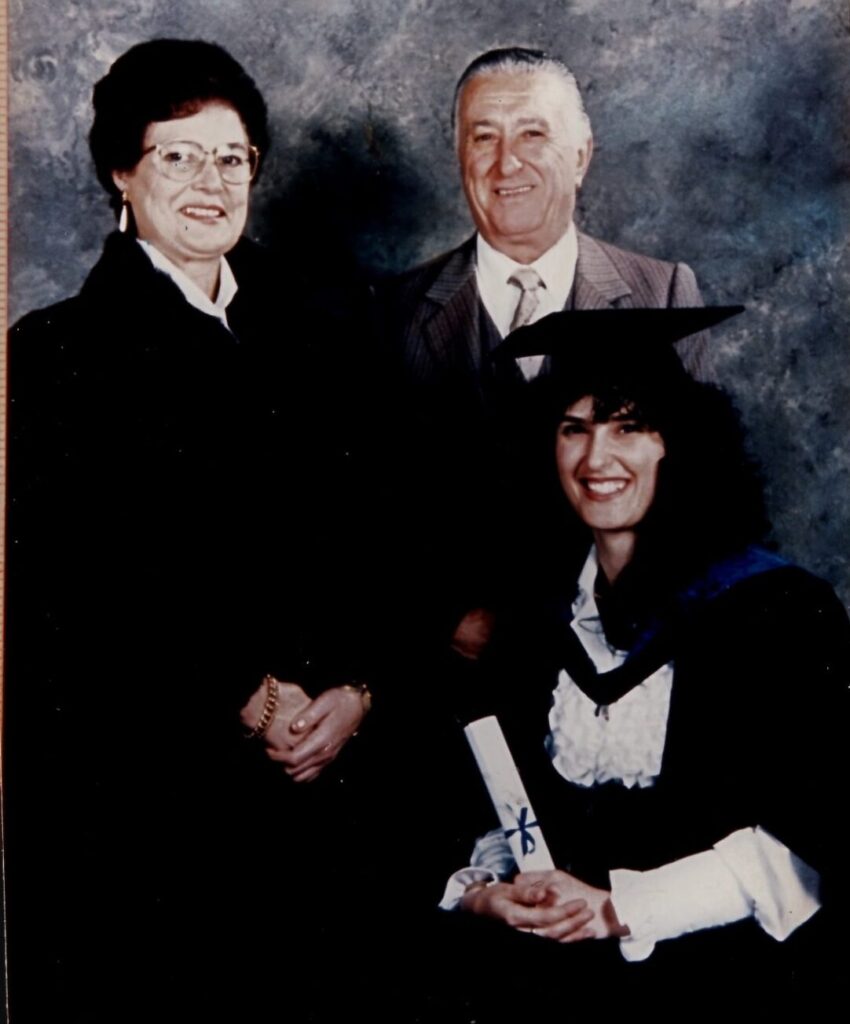

You can probably guess who the boy is, especially if you’ve read the other Bella stories. It’s amazing how many years can pass before we gain deeper insights into those we love.

He never forgot how to speak Italian, and he held this story dear to his heart for the rest of his life. He always spoke fondly of Italy and its people. And he never forgot their common phrase, “Che bella vista!”